Spanish Conquest of Colombia: Gold and Emeralds

In this article

Spanish Conquest of Colombia is the necessary prologue to the Colombian emerald story. In the early 1500s, rumors of abundant gold and green stones lured Spanish parties inland. Unlike Mexico or Peru, there was no single empire to topple-only a mosaic of Indigenous peoples, hard terrain, and scattered clues that wealth lay beyond the Caribbean shore.

Spanish Conquest of Colombia: first coastal forays (1499-1513)

In 1499, Alonso de Ojeda explored the northern coast, from Trinidad and Margarita to Maracaibo and Cabo de la Vela. By 1501, Rodrigo de Bastidas, with Juan de la Cosa and Vasco Núñez de Balboa, traced the Sierra Nevada littoral, the Magdalena River, and the Bay of Cartagena. Early colonies flickered —Santa Cruz in 1502—while Balboa’s 1513 crossing reached the “South Sea.”

From licenses to cities: Santa Marta and Cartagena (1524-1533)

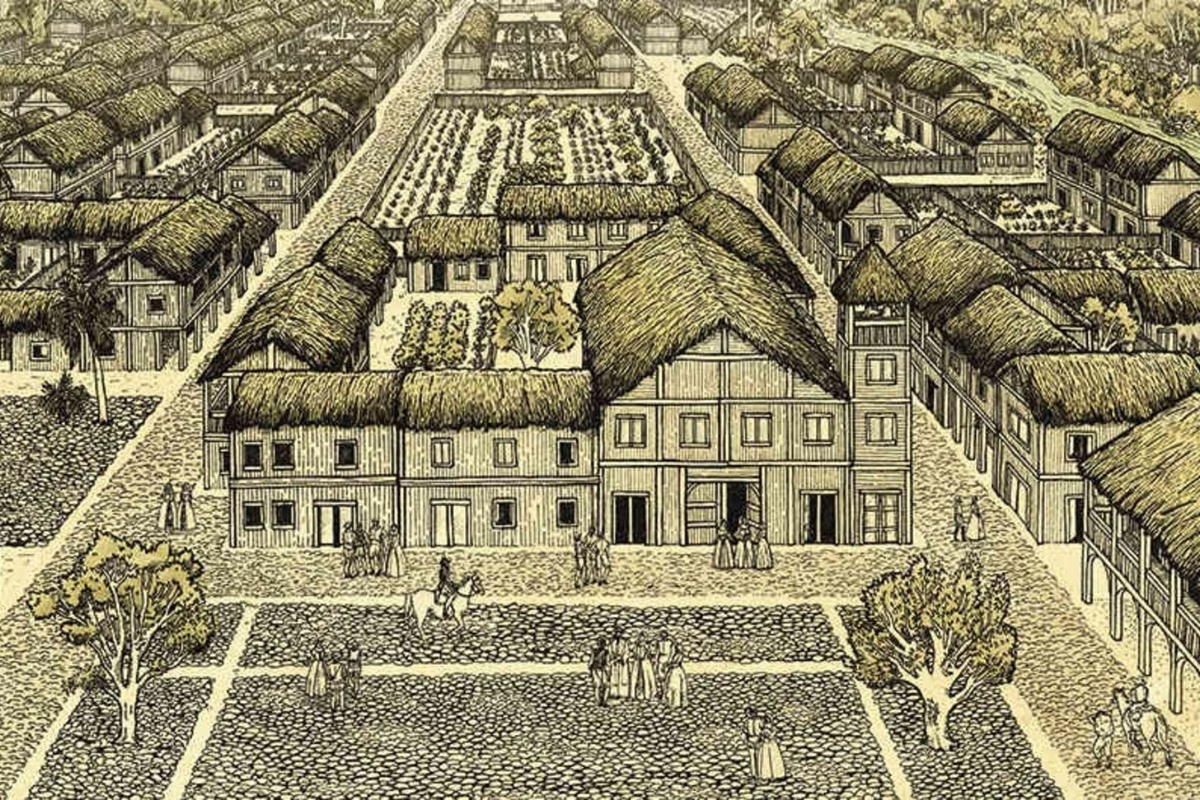

After 1508, the Crown authorized not just exploration but settlement. Jurisdictions shifted; Santa Marta rose in 1526, though violence and disorder followed Bastidas’s death. Even so, the map advanced: in 1531, Pedro de Lerma identified a navigable Magdalena route; in 1533, Pedro de Heredia founded Cartagena de Indias. Tomb finds rich in gold drew more adventurers-and with them, the first steady mentions of emeralds.

Pressure from the Crown and the Magdalena corridor (1535-1536)

Worried by coastal decline as Mexico and Peru pulled men away, the Crown named Pedro Fernández de Lugo governor of Santa Marta in 1535. He arrived in January 1536 with a thousand men to shortages and resistance. Skirmishes followed; victory brought neither food nor treasure. Amid chaos and desertions, the need for a bold inland move became impossible to ignore.

Spanish Conquest of Colombia: El Dorado rumors and the push inland

In the late 1520s and early 1530s, the conquistadors began to hear rumors from the indigenous people about a certain “El Dorado.” Described as a “golden man,” the rumor spread and was quickly distorted into a mysterious city made entirely of gold. The conquistadors, hungry and having found little wealth on the coast, began to consider an expedition inland. From their Caribbean anchorages, the routes up the Magdalena River promised access to the highlands, where the real wealth might lie. Cities such as Santa Marta and Cartagena went from being terminus points to springboards into the interior.

The beginning of the quest for gold and emeralds in the Spanish Conquest of Colombia

Abandoned by his allies, including his own son, and running low on supplies, the governor of Lugo ordered his lieutenant Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada to head south, driven by stories from the natives about an immensely wealthy people living in a mysterious city of gold in the mountains and possessing mines extremely rich in emeralds. The journey that followed would redefine the history of Colombia’s green stone.

Have a question, correction, or insight to add? Share it below. We read every comment and moderate for clarity and civility.