Somondoco Emerald Mines: Colonial Rule and Decline

In this article

Somondoco Emerald Mines form the next chapter after Quesada’s march. Once the Bogotá plateau fell, the Spanish dismantled Muisca authority and imposed a new order. Without a unified native state to negotiate, power shifted quickly to colonists who sought gold and emeralds across fields, workshops and the mining zones once overseen by the zaque of Hunza.

Somondoco Emerald Mines under the encomienda system

When the Muisca confederation was dissolved, the defeated chiefs were deposed and the nobles stripped of their privileges and wealth. Under the encomienda system, the Muisca communities were assigned to Spanish landowners under the pretext of protection and evangelization. In practice, this meant heavy tributes (food, cotton, gold, and emeralds) and forced labor. Many of them were sent to the slopes of Somondoco to feed the colonial ambitions of the Spanish crown.

Water, disease, and the limits of extraction in Somondoco emerald mines

Mining in Somondoco faced a major constraint: water scarcity. In a region where reliable washing and transportation were difficult to ensure, production remained modest even as demand for labor increased. New diseases like smallpox, measles or influenza ravaged the workforce, and the brutal pace of work in the fields and mines accelerated the demographic collapse, undermining any hope of sustainable production.

Looting, ransoms, and shifting priorities

While Somondoco was being mined in the 1540s and beyond, many Spaniards preferred quicker gains by looting Muisca tombs, seizing ritual objects, or demanding ransoms from elite families in exchange for gold and emeralds. With easier gains outside the mines and rumors of richer veins to the west, colonial attention turned to a more promising frontier: Muzo.

Reform on paper, exploitation in practice

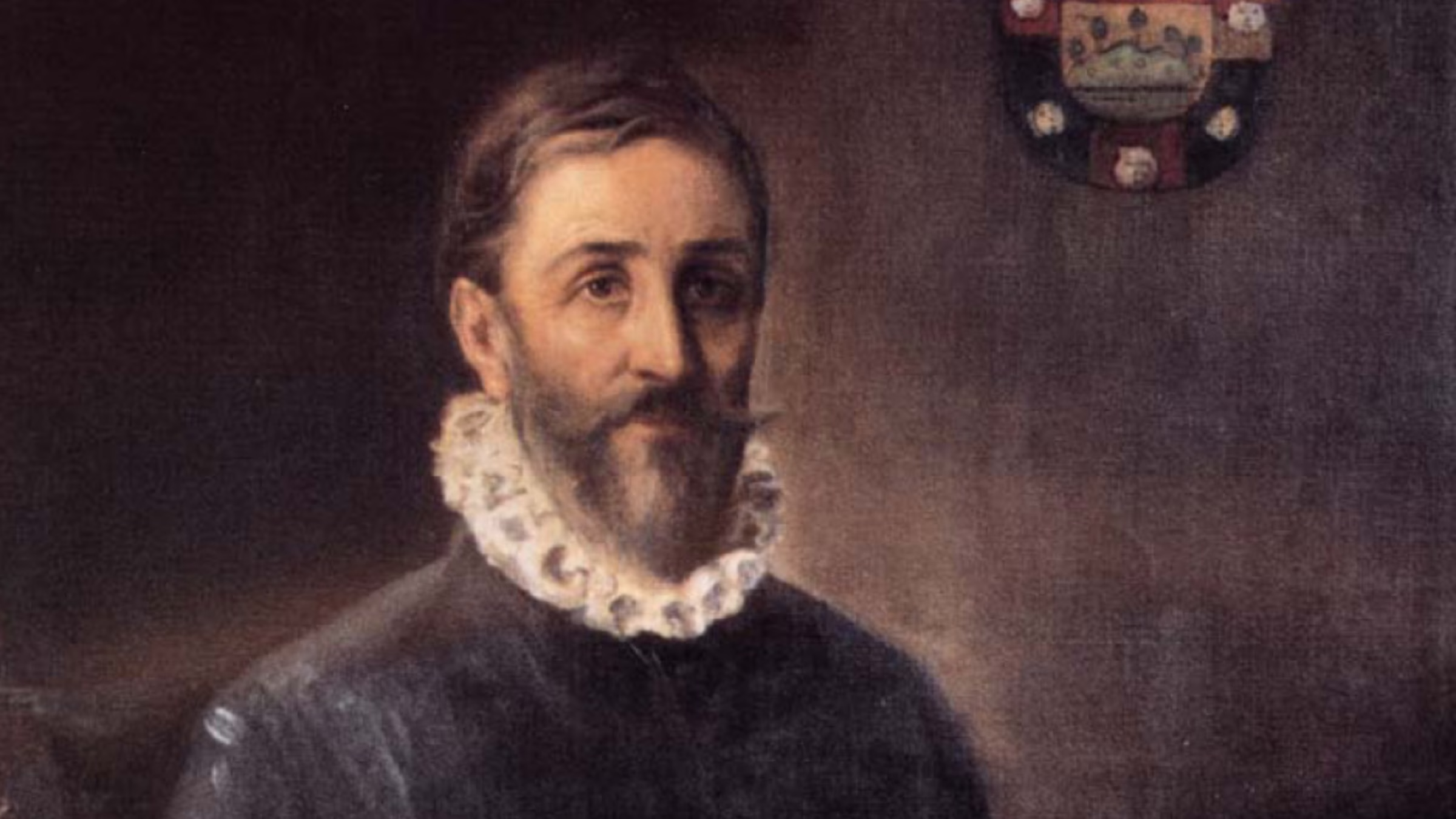

Voices such as that of Bartolomé de Las Casas put pressure on the Crown, and the New Laws of 1542 sought to put an end to abuses against the indigenous peoples. But in the New Kingdom of Granada, their implementation was slow. On the ground, the encomenderos retained control, and the work of the indigenous people in Somondoco changed little: more orders, more tributes, little protection, and still meager incomes from emeralds.

Disappearance of the archives and end of Somondoco

In the 1560s, attention turned to the west and activity in Somondoco declined. Later authors mentioned a royal order from Charles II to close the mines, but no official document confirms this. What we do have is a report from 1772: Somondoco was abandoned, its entrances lost in vegetation, its map of tunnels forgotten. For nearly two centuries, knowledge of the work sank into legend.

Have a question, correction, or insight to add? Share it below. We read every comment and moderate for clarity and civility.