Muzo Conquest: War for Colombia’s Emerald Mountain

In this article

The Muzo conquest began after that of the Muiscas and the Somondoco mines, when the Spanish heard of a country even richer in emeralds to the west. Their attention shifted from the Tenza Valley to the rugged valleys of western Boyacá, lands held by the fiercely independent Muzo people, who were fiercely independent and, according to rumor, hid a veritable “mountain of emeralds.”

The conquest of Muzo after Somondoco: rumors turn into roads

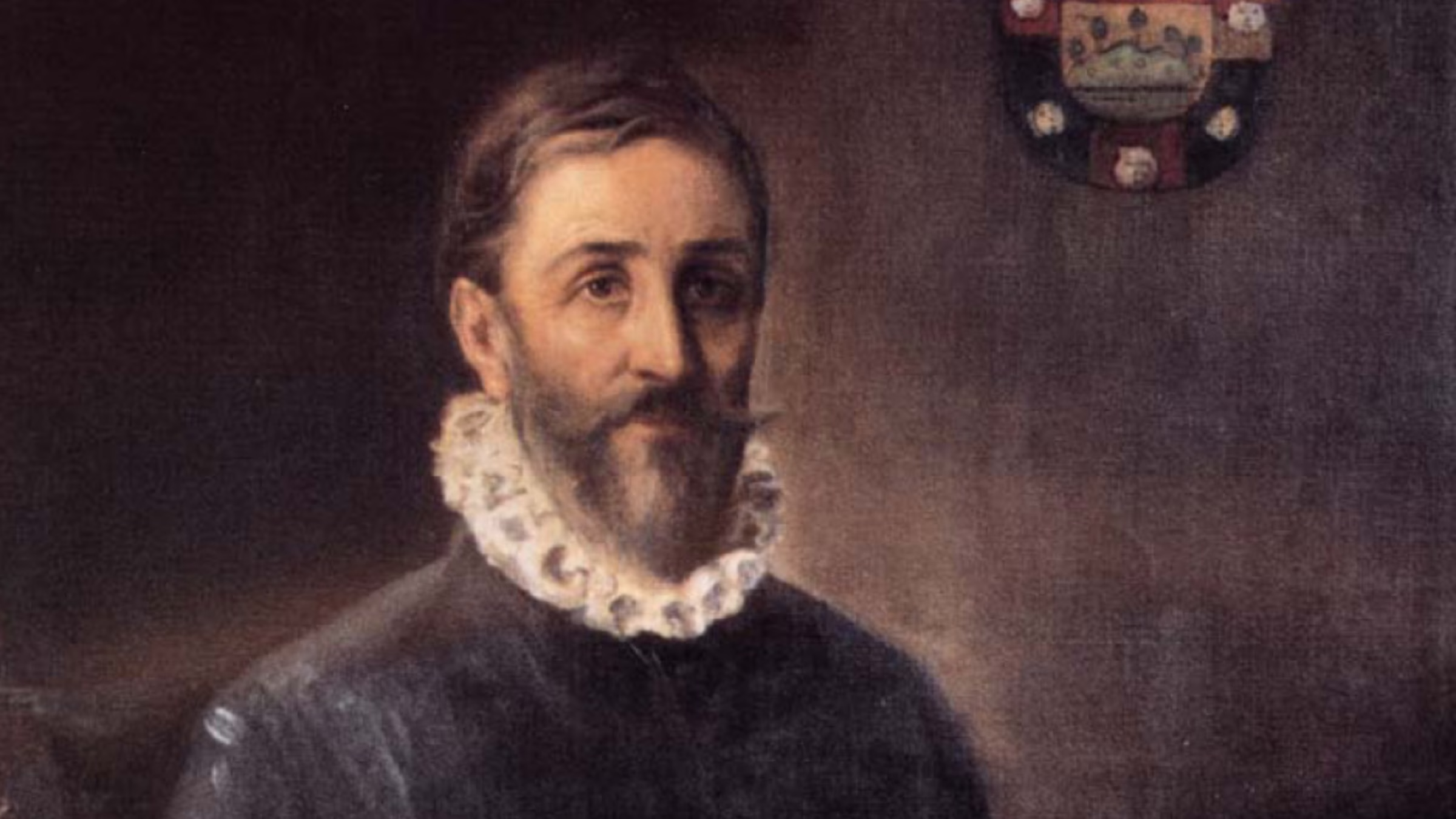

In 1537, as they advanced through Muisca territory, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada’s men confirmed the existence of active emerald mines in Somondoco and seized gold and precious stones in Guachetá, Suesca, and Nemocón, among other places. However, the richest deposits were beyond their reach, further west, in a territory controlled by the Muzos, where the legend of the emeralds focused Spanish ambitions.

In Muzo territory: twenty years of resistance

At the end of 1538, groups left Santa Fe de Bogotá to travel to these “unexplored” lands. Compared to the relatively quick subjugation of the Muiscas, the campaign against the Muzos proved difficult: the rugged mountains, rainforest, and guerrilla tactics caused setback after setback, and the people refused to reveal the location of their mines or cede their territory.

Early failures: Lanchero and others (1539-1551)

The campaign led by Luis Lanchero in 1539 failed; the Muzos were organized and the conquistadors ill-prepared. Subsequent expeditions such as those of Diego de Martínez (1544), Melchor de Valdés (1550) or Pedro de Ursúa (1551)—also failed despite more methodical plans. Knowledge of the terrain remained the Muzos’ greatest weapon.

Turning point in the Muzo conquest: the return of Lanchero (1558-1560)

It was not until 1558 that the tide turned. Lanchero returned with a better knowledge of the country and a more rigorous strategy, collaborating with Juan de Rivera to advance methodically through the ravines and forests in a war of attrition. The fighting was long and violent; Lanchero himself survived a poisoned arrow wound before the Spanish finally gained a slight advantage.

A fragile foothold: Santísima Trinidad de los Muzos

In June 1560, Lanchero founded Santísima Trinidad de los Muzos on a terrace overlooking the region, near the richest areas. This post anchored the Spanish presence, but did not end the war: the Muzos’ attacks persisted (night ambushes, secret poisonings) and settlers died. Nevertheless, this foothold finally allowed the Spanish to consider exploring the region in search of the famous emerald mines.

Have a question, correction, or insight to add? Share it below. We read every comment and moderate for clarity and civility.